In 2015, Sally Liza Claro, 42 then, applied for a job abroad to provide for her family. But when she arrived in Lebanon, she was trapped into domestic servitude without pay, stripped off her labor rights, and had no means to go back to the Philippines.

“I never imagined that my dream for a better life would turn me into a victim. It was only later that I realized that what happened to me was already human trafficking,” Sally said.

Trafficking in persons or human trafficking remains a pressing issue in the Philippines, despite the existence of anti-trafficking in persons laws. According to the 2024 Trafficking in Persons Report of the Philippines by the US Department of State, the government has identified 890 victims of sex trafficking and labor trafficking and 1,134 victims of unspecified exploitation.

However, Balay Alternative Legal Advocates for Development in Mindanaw, Inc. (BALAOD Mindanaw) stated that this does not accurately reflect the true number of cases.

“The data only includes the cases that were filed. What about the cases that weren’t filed? These are still cases of trafficking; they just weren’t reported,” Maryland Gargar, BALAOD’s Women and Children Protection Program Head, said.

Despite this, survivors, communities, and advocates are working together to end human trafficking and empower victim-survivors towards justice and healing.

A Dream Turned Nightmare

In 2015, Sally was enticed to work abroad to provide for her family’s needs and to support her children’s education. She applied as a hotel receptionist in Lebanon through a recruitment agency in La Union.

Red flags were everywhere. She never saw her employment contract until they were already at the airport, and she was instructed to line up at a specific immigration booth. When she opened her contract on the plane, she saw that the job order was for a domestic helper.

When she landed in Lebanon, she was picked up by a woman who hardly speaks English. She was taken to a business and household compound where the start of her nightmare would begin. Sally would take care of the woman’s child and bedridden mother, be an English tutor to another child, while also doing household chores.

“You’re lucky if you get three hours of sleep, and they barely fed me at all,” Claro said.

Her passport and mobile phone were taken, and Sally has no contact with her family. Fortunately, Sally met a fellow Filipino working there who helped contact her family so she could go home. Little did she know that her family was already looking for her, and she had already been declared a missing person.

It was only in October 2016 that Sally was rescued by the Philippine Embassy. During the rescue operation, a physical altercation broke out, which urged her employer to file a case against her.

After a month of hearings, it was decided she would be deported, and she got detained in the Lebanese immigration for three months, where she spent her Christmas and New Year. There, she saw that others had experienced worse – one was burned by an iron, one had a broken leg, and another got pregnant.

“That’s what gave me strength. I told them that if I get the chance, I’ll help them,” Sally said.

In February 2017, Sally finally arrived home in the Philippines. “When my husband saw me, he cried. But I told him, ‘I’m alive. I made it home safely, but we need to help the people I was with.’” Sally said.

From Survivor to Advocate

Kanlungan Centre Foundation, a legal empowerment organization that works with migrant workers, helped with Sally’s reintegration process. She would undergo psychiatric treatment and capacity-building sessions with other victim-survivors.

These victim-survivors became a family. Little by little, they are being healed by each other’s comfort and company. Even when the training was done, they continued to support and communicate with each other. This is when the Balabal Organization – Support Group was born. Sally would then become co-founder and president of the organization.

“I don’t want my fellow Filipinos to experience what I went through, especially when I got detained,” Sally said.

Balabal would start referring probable cases of human trafficking to Kanlungan. Members would also attend paralegal training where they would learn about their rights, case documentation, and laws related to trafficking in persons. Balabal was able to help eliminate all the illegal recruitment agencies in La Union.

Community Action in Mindanao

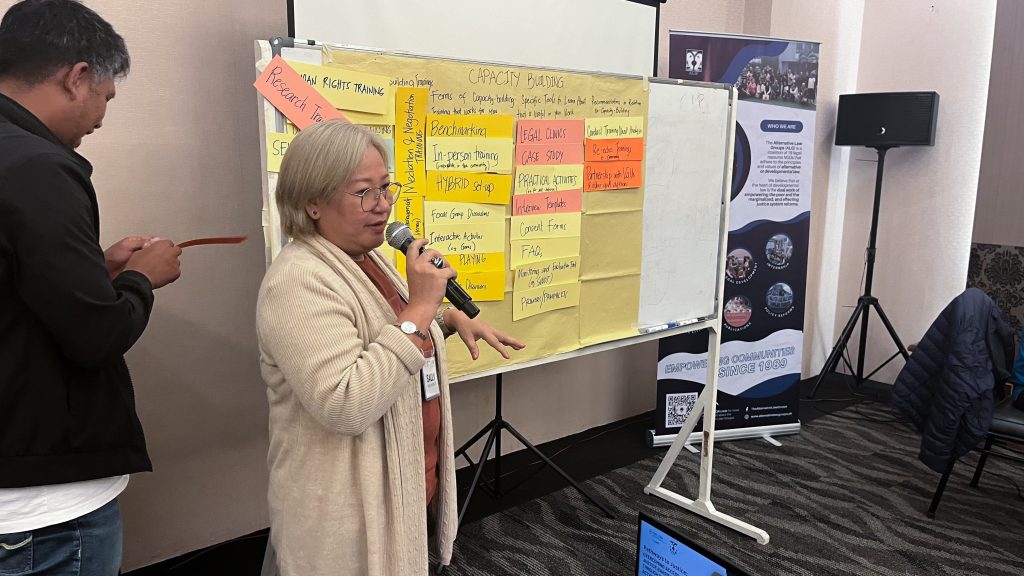

Around the same time Sally left the Philippines in 2015, the call for a bigger and proactive advocacy against human trafficking in Cagayan de Oro City in Mindanao was brewing. Based in the city, BALAOD took the challenge and started designing a legal empowerment program related to trafficking in persons.

“Based on meetings with networks and local sectoral bodies, one strategy to prevent and combat this is legal awareness, so that’s what BALAOD did,” Maryland said.

In Cagayan de Oro, most cases involve sexual exploitation; some victims are as young as two years old. Based on BALAOD’s experience with handling cases, many would start online and then escalate to physical sexual exploitation.

BALAOD started with legal awareness caravans in schools, targeting students from Grades 8 to 10. Today, they have expanded to spread awareness with Indigenous Peoples’ communities, out-of-school youth, and women’s groups.

They also conduct night caravans targeting workers in entertainment establishments, such as bars and spas. This is led by victim-survivors trained by BALAOD on anti-trafficking in persons and anti-online sexual abuse and exploitation of children (anti-OSAEC) laws.

“They printed flip tarpaulins and used those during the discussion. While that’s happening, some participants are doing their makeup, getting ready, or doing a client’s manicure. Other times, they’re in the middle of a massage spa where they just pull the curtain aside to make enough space for the spa attendants to sit,” Maryland said.

Towards a One-Stop Support System

BALAOD is also a part of a loose network of individuals and organizations called Kagay-anon Against Sex Offenders (KASO). KASO was created during the peak of the case of Australian child trafficker Peter Scully, where many civil society organizations (CSOs) and child rights advocates gathered together to proactively monitor the case.

KASO would then advocate for a one-stop shop for victims of trafficking in persons that would be based on the Northern Mindanao Medical Center (NMMC)’s Women and Children Protection Unit, where many cases of gender-based violence were referred to.

Ideally, the one-stop shop will cater to all the needs of the victim, eliminating retraumatization and the need for them to go from one agency to another. In the one-stop shop, a victim will have access to a social worker, a police officer, a medical worker, and a lawyer or legal resource NGO.

“If our advocacy is trauma-informed, you don’t make a victim repeatedly retell what happened to them,” Maryland said.

This initiative was endorsed by the Regional Inter-Agency Committee on Anti-Trafficking and Violence Against Women and their Children (RIACAT-VAWC) and is currently a work in progress, but the commitment of government agencies has already been secured.

Every Wednesday, BALAOD is present at the one-stop shop to provide for the legal needs of victims, liaising with police officers and social workers to collaborate on case information.

Hope, Justice, and the Power of Survivors

A better implementation of anti-trafficking in persons laws and a harmonized response from government agencies is needed. “There is a lack of systematic convergence among the agencies mandated to respond to victims. The responses are fragmented,” Maryland said.

“If they truly care about the people they call ‘heroes,’ then they should do what’s right. They should protect them,” Sally said. The Philippine government is known for calling overseas Filipino workers (OFWs) modern-day heroes.

Both Sally and BALAOD hope for victim-survivors to be at the forefront of the fight against trafficking in persons.

“When you have a victim-survivor actively sitting in and lobbying, the policies created by those in power will be more contextualized to the needs of the victims,” Maryland said.

“We hope that everyone we’ve helped will also become a voice for raising awareness on human trafficking, so that no one else becomes a victim. Don’t be afraid to fight for your rights,” Sally said.

She wants to remind victim-survivors that there is hope, as stated in Balabal’s motto: “Noon ay sawi, ngayon ay wagi,” which translates to “Once defeated, now triumphant.”

![[ENG] Breaking the Silence: Healing the Unseen Wounds of Disaster-Affected Communities](https://alternativelawgroups.ph/wp-content/uploads/2025/12/Braveheart-Photo-400x250.jpg)

![[ENG] From Refugee to Rights Advocate: How a Paralegal Became the Voice of Justice in the Camp](https://alternativelawgroups.ph/wp-content/uploads/2025/12/Image-9-400x250.jpg)

![[ENG] Capturing Equality in Capiz State University, Fighting for Trans Students’ Right to Dream](https://alternativelawgroups.ph/wp-content/uploads/2025/12/rrights-400x250.png)